The company logo, the brand colors, it’s an important choice for every company. Global companies spend massive amounts of money on picking the ‘right’ color. However, there is a rather fundamental issue with choosing a brand color: how do you select it? What is your basis? And how do you define that precious color you carefully picked?

CONTENTS: The Chain of Tool Tolerances | A good practice: measure and verify! | Why is this important? | Update

As you may have noticed, I’ve written several articles on brand colors in the past, highlighting different aspects. And while preparing a paper and video presentation for the TAGA conference, some more pieces of the puzzle fell into place.

I guess most people select the new brand color from a visual sample, certainly not from a series of numbers (either CIELab or spectral numbers). And that’s where things might go wrong…

If you have read my article on the chain of tool tolerances, you might be familiar with the deviations in Pantone guides. Some 90% of the colors are within a 2dE00 from the ‘master color’ (a reference in spectral values). Which means 10% is outside that 2 dE00… Do you know which colors have a higher tolerance? I don’t. Pantone doesn’t publish information about that.

So when looking at a Pantone guide and picking that perfect color, 1 chance out of 10, that color you are looking at has a higher than 2 dE00 deviation from the master color. Which brings us to a fundamental question: what color (definition) do you use as your perfect brand color? The one you looked at? Or the master color that it should represent? Think about that: the master color might be (slightly) different… Now in case you argue that it’s only a tiny difference that won’t make a difference in real life: please be consistent and don’t demand a super tight tolerance from your printer…

Would it be better just to measure the chosen perfect color and use that as the standard? And describe it as a CIELab or even spectral value? Well… there is another issue: measurement devices are not perfect. These also have deviations, the inter-instrument agreement (same brand, same type) could be up to 1 dE00. And you should measure it the right way (and it would not be a bad idea to take multiple readings and average them).

Does this seem too abstract or too far from reality for you? Well, just check the test with measurements of Pantone guides I published a few years ago… The origins of the deviations were either the guides, or the measurement devices used, or a combination of both.

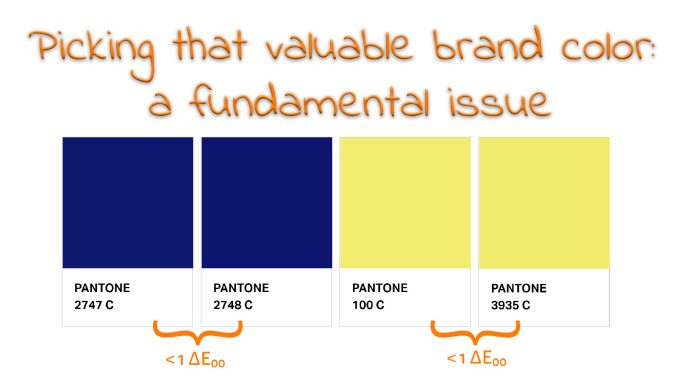

And I also checked the values of some Pantone numbers. Let’s say you had a somewhat heated discussion in the team about whether to choose Pantone 2747 C or 2748 C. Eventually, you picked 2747 C; you know, it’s just that tiny difference that makes it more appropriate for your brand. The digital values of those two colors are less than 1 dE00 apart (0,75 dE00 according to the values in Pantone Connect). This could mean that the printed version of 2747 C has a higher deviation from the master data than the difference between both printed colors… That is: if the blues happen to belong to the 90% of colors that are within the 2 dE00 tolerance…

Another example is Pantone 100 C and 3935 C, there the difference is 0,66 dE00 (based on the Pantone Connect values)… And for the record: it didn’t take me much time to find these two examples, only a few minutes. (* see update below!)

A good practice: measure and verify!

If you choose your brand color(s) from physical samples in a Pantone Color Guide, it’s probably good practice to measure and verify these measurements with either the official Pantone values, or if you don’t have access to that, with the values in Adobe Photoshop. But do this according to best practices: use a decent spectrophotometer, one that is well maintained and recently calibrated. Take multiple, e.g. three, measurements and average the results. If possible, check with a second decent, well maintained and recently calibrated spectrophotometer, one from another brand than the first one would be interesting.

If the measurements show a (significant) deviation from the ‘ideal’ values, you might want to use the measured values as your brand color. And even when the deviation is small, it is always better to have a scientific description of your precious brand color(s) than a notation in a non-scientific color system.

Why is this important?

We need to get honest about brand colors: with a vast number of sometimes just slightly different colors in color guides, one might get the impression that those tiny nuances matter a lot in real life and that a very narrow tolerance, very accurate color reproduction is a piece of cake. It is not. The tolerances of printed color guides compared to the master data can be higher than the ‘space’ between two separate colors in that guide. Also, the deviations between measurement devices might be larger than the space between two separate colors.

A heated discussion on the difference between Pantone 2747 C and 2748 C and why the first best matches your brand is just a waste of time and energy.

BTW: as I’ve shown before, people only remember large categories of colors, certainly not the magnitude of differences as between Pantone 2747 C or 2748 C.

UPDATE 05/07/2023: I have updated a small part of this article (including the header image), after a discussion during a Fogra webinar. The original colors were checked in Adobe Photoshop. However, what I didn’t know at that time: the Pantone libraries in Adobe CC applications are/were outdated. Along the way, the Lab-values had changed. And although the Pantone and Pantone+ libraries were still available, the colors were NOT the same as in other Pantone libraries… Plus: in Adobe CC applications, no digits are shown and the rounding can lead to incorrect calculations when talking about small deviations.

So, to update and correct this, I checked the values in Pantone Connect, the one that designers will use to access Pantone colors. And although the deviations are a bit higher than in the original calculation (especially the yellow one), they both are still below 1 dE00: 0,75 dE00 for the two blues, 0,66 dE00 for the two yellows. Which means: my main point is still valid, some colors are just too close (< 1 dE00), much closer than common tolerances used in print… Even smaller than the tolerance aim that Pantone uses: 2 dE00.

Is that SMS website dead? I see many dead linsk amd design looks from the 90s. I see this article is quite new, but cant really find info about libraries on their site