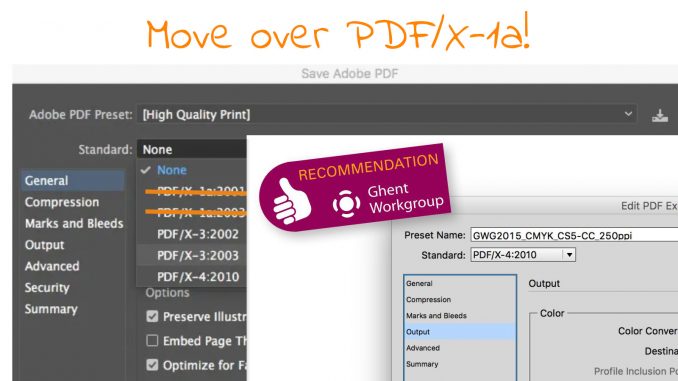

It was a surprise when I read the recent message from the GWG: ‘Stop using a 20-year-old standard’! My first reaction was: what??? The GWG promotes standards! But then I noticed the ‘20’, and it all started to make sense… But too many people don’t seem to get it why changing to a newer one will benefit them.

CONTENTS: GWG | PDF: different versions | Different flavors | Using the full potential of your press | Why is this important?

If you don’t know the GWG, you should definitely check their resources. It’s a group of specialists, from all over the world, that shares specifications, application settings, and tools to improve the creation, exchange, and processing of PDFs in print workflows. The old name used to be the Ghent PDF Workgroup, but they dropped the PDF several years ago. I’ve always supported the work of the GWG; in my previous life, I was actively involved in the GWG for a long time. So I know what they are doing very well, and can only encourage everyone to look at their work. You will benefit from it. The GWG should become your BFF.

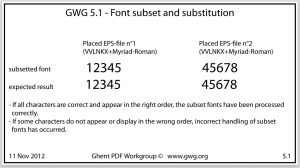

Below is one of the patches of the GWG test suite. And the story behind it is interesting… A printing company contacted me: one of their customers accused them of changing numbers in technical drawings in a catalogue. It was a large print job, if my memory doesn’t fail me, it was over 300 pages, hard cover, 10.000 copies. And because of those wrong number in these technical drawings, the customer rejected the print job. It didn’t take me long to find the problem: font subsetting, where something unusual had happened. And together with my former colleague, we put together this test patch. BTW: both the designer and the printer were to blame, neither of them had updated their software, both worked with the initial (dot zero) version. If they had updated both the PDF creator and/or the RIP, the problem would not have occured. On the PDF creator side, the subsetting would not have been unusual, on the RIP, the weird subsetting would have been caught.

PDF: different versions

The ‘Portable Document Format’ was introduced over 30 years ago, in January 1993. And it would revolutionize how we exchange documents. Why? Among others, because of its ‘portability’. A PDF file has everything included to show it as intended. Text, images, and even fonts are included. Especially that last one was a big jump forward.

It was Adobe who created the PDF file format. With every new version of Acrobat, they also released a new version of the PDF file format. Specifications were also made available to the rest of the world. Eventually, in 2008, Adobe decided to make it into an open format and handed the further development of PDF over to the ISO.

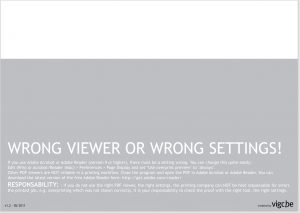

With every new version of PDF, new features were introduced. To name just one: transparency. This was introduced in PDF version 1.4, launched alongside Adobe Acrobat 5 in 2001. The interesting thing about PDF is that it is backward compatible: you can open a PDF v1.4 with Adobe Acrobat 4. You will not get an error message. And it will show everything it knows correctly. But things it doesn’t know, like that transparency, it will either not show this or not show it correctly. And that’s where it went wrong in the early 2000s… At that time, when seeing a lot of issues with this, I created a small tool – essentially a PDF with transparency – to check whether a suitable viewer and the correct settings were used.

Plus, not all PDF viewers implement the complete PDF specifications… The entire v1.7 specification is 1.310 pages… That’s why some PDF viewers are ‘lighter’ than Adobe Acrobat Reader: they just implemented the most basic stuff. Which means: it might not show a PDF correctly.

Different flavors

The PDF specification is very broad. If you are in a specific market, there will be a lot of features you don’t need. That’s why for specific applications, a subset was created. On the Adobe website, the following are mentioned: PDF/A (archiving), PDF/E (engineering and manufacturing), PDF/X (printing), PDF/VT (variable data), PDF/UA (universal access, includes assistive technology enhancing readability), PAdEs (PDF Advanced Electronic Signatures), PDF Healthcare. Most of these are ISO standards, including PDF/X: ISO 15930 – ‘Prepress digital data eXchange’.

The first version of the ISO standard PDF/X was launched in 2001. The complete title is: “ISO 15930-1:2001(en) Graphic technology — Prepress digital data exchange — Use of PDF — Part 1: Complete exchange using CMYK data (PDF/X-1 and PDF/X-1a)”. As you can see in the title, this limits the exchange to only CMYK data, not RGB. Plus, it is based on PDF v1.3, so that nice transparency can not be in the PDF file, you need to deal with that during PDF creation. Which is not the optimal solution (it works, but it limits what you can do with it later in the process).

After PDF/X-1, newer versions were released, based on newer versions of the PDF file format, but also with the support of RGB and even CIELAB. NChannel channel color spaces (important for Extended Color Gamut printing, like CMYK+OGV) is supported in PDF v1.6 and higher, the version on which PDF/X-4 is based.

And here you have three important reasons why you should move on from PDF/X-1a: transparency, RGB, and NChannel color spaces. But in the GWG webinar, you will hear a lot more reasons!

Using the full potential of your press

In case you are wondering what this could mean for you, as a print service provider, here’s an important one: using the full potential of your presses, especially if you have digital presses… Maybe you never checked it, but if you have a digital press that’s not a decade old, it might have a larger gamut than the standard offset press (e.g., PSO coated v3). And that’s where a PDF with RGB images could make the difference…

At this moment, if your customers need to deliver a PDF/X-1a, it will only contain CMYK data. The conversion of images from RGB to CMYK will be done before or during PDF creation. And that’s the data you need to work with, the input for your digital press. That conversion will be done with a profile like PSO coated v3 (of the older ISO coated v2). If your digital press has a larger gamut, if your press has the capabilities to print more vibrant colors, that information is lost. Meaning: you will be limiting the output of your machine.

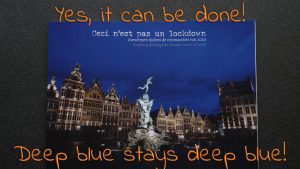

If you would accept PDF files that still include RGB images, you could make the conversion to CMYK and get the most out of your press. And to make it very concrete, I published a photobook a few years ago, with lots of deep blues. With the regular CMYK profiles, this looked very bad. But I found out, thanks to Jubels Printing, that the Xerox Iridesse had a much larger gamut, which could reproduce those nice deep blues… If you have a recent digital press: check what it is capable of! Maybe you can offer much more colorful prints than you do at this moment…

Sidenote: I have to admit, it’s possible that I did provide a CMYK PDF to Jubels, but the conversion was done with a different profile: XCMYK, which has a larger gamut.

There could be a discussion on one point when every printer would accept PDF files with RGB color data and then convert it to the full potential of the press: when the same job gets reprinted at another printer, it might look a bit different. Is that important? That’s for the print buyer to decide.

Why is this important?

If we had never changed how we worked, we would still be in the Stone Age. Literally. PDF/X-1a was a huge step forward in the days it was introduced, but technology and the PDF file format have evolved. We need to take the next step. And the GWG offers all the information and tools to take that next step. Listen to their webinar. Use their application settings, use their tools to check your PDF workflow. It’s all for free…

The GWG webinar was on Tuesday 23 January 2024, below is the recording.

Hi Eddie

I believe that changing to a PDF x4 format should be encouraged but with some caveats:

1. The colour space should the chosen CMYK profile rather than depend on the PSP to convert RGB images to the PDF CMYK outputintent. This is because the PSP may use diferrring colour management settings in their PDF workflow for image conversion, rendering intents and BPC being come to mind.

2. The PSP must have and use the latest version of the Adobe PDF Print Engine, or simliar, within their CtP workflow or DFE. Otherwise PDF X4 features such as transparency may not be processed correctly.

So to sum up, if changing to PDF X4 from PDF X1a and conversation with your PSP will be needed.

Paul Sherfield

If you delivered your PDF in CMYK format – say to Fogra 39 then I don’t see any reason for a conversion of any kind. If you told them that you wanted vibrant colours first and foremost I guess they simply replaced the destination Fogra 39 icc profile with the XCMYK icc profile and printed the job (preserving your CMYK values).

All XCMYK does is to boost the CMY inks – in the case of offset you simply increase the density considerably to push the gamut.

No Ingi, you are wrong. XCMYK uses a different conversion to CMYK compared other ICC profiles, it’s not just ‘more ink’. All other profiles I checked, changed my deep blues into purple. XCMYK was the only one that kept the blue blue. Just try it yourself.

(see also this article: https://www.insights4print.ceo/2020/04/xcmyk-vs-cmyk-heres-your-business-case/).

Hi, I agree that we shouldn’t use old standards, and rather prefer newer ones. However, one important reason to still use the old formats is: compatibility. For instance, MS PowerPoint or MS Word do not properly handle newer PDF versions, resulting in distorted representations of PDFs… I’m forced to use PDF/X-1a:2001: or PDF/X-3:2002 (which are PDF-1.3). Newer versions will cause serious problems. (I’m on MacOS)

Good point Norman!

But to put everything into context: this article is about print ready PDF files, the ones that creatives make and supply to their printing companies. I don’t think people will use these kind of ‘heavy’ files for PowerPoint or Word.